Bruce Jenkins: Will Clark’s Legendary Career Belongs in Cooperstown

The following piece by sports writer Bruce Jenkins was published in the San Francisco Chronicle on September 3, 2021.

SF Chronicle Editor’s note: Through the Baseball Hall of Fame induction ceremony on Wednesday in Cooperstown, N.Y., the Sporting Green will present some of its writers’ arguments for which person, given the chance, they immediately would induct.

How does someone become a legend? As described by the Collins English Dictionary, it’s “a person whose fame or notoriety makes him or her a source of exaggerated or romanticized tales or exploits.”

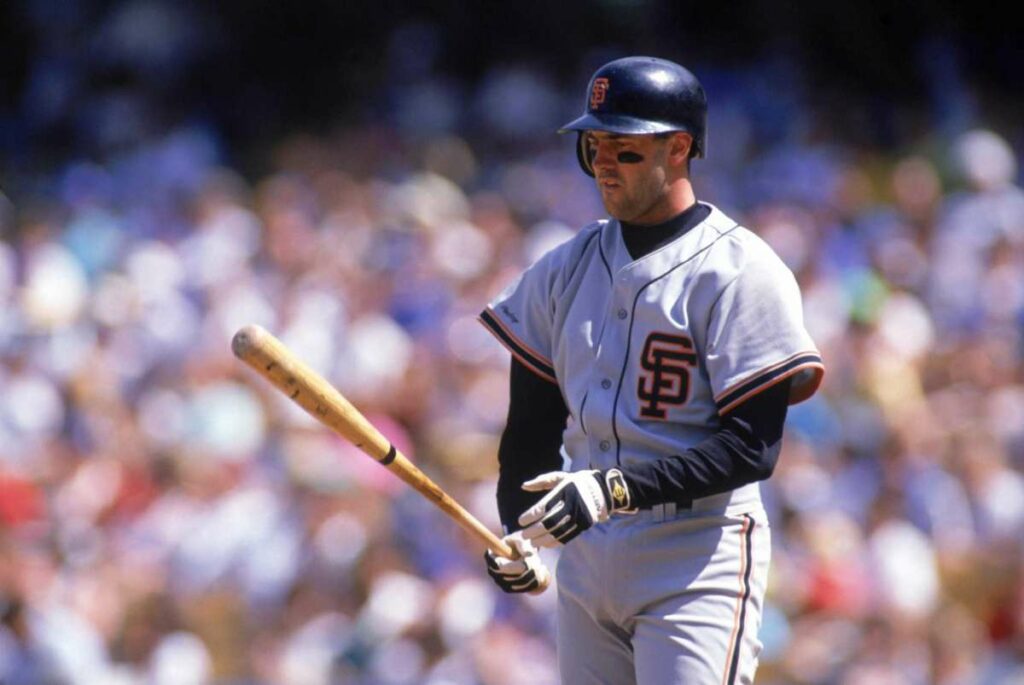

Be our guest, Will Clark (Jesuit High School Class of 1982). You’re as legendary as they come.

Go heavy on the romance and don’t worry about stretching the truth, for we know this story well. Clark should be in the Hall of Fame because his career accomplishments were just as distinctive and spectacular as we remember them.

I was especially gratified to have a Hall of Fame vote in 2006, when Clark’s name first appeared on the ballot. And I was perplexed to discover that he got only 4.4% of votes from the Baseball Writers’ Association of America — short of the 5% required to grant him another chance. His name didn’t surface again until December 2018, when he was voted down by a Today’s Game ballot of the Veterans Committee.

Just like that, his candidacy vanished. Perhaps he shouldn’t feel too badly; a number of great players haven’t made the Cooperstown cut. (Thurman Munson, Don Mattingly and Keith Hernandez come quickly to mind.) But Giants announcer Jon Miller put it best when he said, “Will Clark should be in. He’s what the Hall of Fame is about.”

In the realm of hard evidence, Clark had everything it takes during his years with the Giants (1986-93): five All-Star appearances, a Gold Glove, two Silver Slugger awards and a second-place finish in the MVP race in 1989, when his NLCS performance against the Cubs stands with the greatest postseason episodes in history. Add “best damn hitter in baseball” and you weren’t far off, not to those who truly understood the game. Tony Gwynn loved to rave about Clark’s swing, and there were times when Barry Bonds spoke with wide-eyed amazement about the man’s talent.

What’s surprising is the perception that it all ended in San Francisco, that he didn’t perform long enough. Well, he played 15 seasons, which is plenty. Injuries became a recurring handicap, but he posted nothing but .300-plus batting averages (save 1996) in his years with Texas and Baltimore, and when he joined St. Louis in a midseason-2000 trade, he bowed out of baseball after hitting .345 in 51 games with the Cardinals, helping them reach the postseason. He retired with a .303 lifetime average (.333 in 31 postseason games), leaving on his own terms to maximize time with his wife and 5-year-old son, Trey.

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly what separates legends from standard greatness. It often comes down to style, a certain set of mannerisms. And there was a well-meaning arrogance to Clark, boisterously raw and unfiltered, leaving him bereft of decorum or tact. He was deep-down Louisiana country all the way, with a high-pitched voice that stirred many a clubhouse mood. And once teammates learned his middle name, they came up with “Nuschler face” for his variety of scowling facial expressions. He wasn’t a showman but rather a natural show, and original to the core.

From the moment he showed up for the Giants’ 1986 spring training, Clark knew he was great — because he’d always been great: state championship team at New Orleans’ Jesuit High School; World Series star at the Babe Ruth, American Legion and collegiate levels; best hitter on the storied 1984 Olympic team filled with future major-leaguers. His first at-bat as a Mississippi State starter? Home run. First professional at- bat for the Giants’ Fresno farm club? Home run. And, man, was he chatty. Teammates were known to grow weary of his relentlessly upfront presence at times, but as Al Rosen (the Giants’ general manager from 1985-92) often said, “If you had 25 ballplayers like Will Clark, you’d never have to worry about winning.”

When he stepped to the plate against the great Nolan Ryan at the Houston Astrodome for his first big-league at-bat, Clark puffed a little balloon out of his bubble gum, then reeled it back in, confidently looking out at the mound like a foreman surveying his construction crew. Ryan started him with a curveball for a called strike and Clark couldn’t help but smile, feeling he’d been granted a measure of respect. He let a high fastball go by for a ball. Then belted a chest-high blazer over the center- field fence. Legendary.

There was so much more to come. Tagging the Cubs’ Greg Maddux for an RBI double, solo homer and grand slam as the Giants won Game 1 of the 1989 NLCS at Wrigley Field. Providing the greatest baseball moment in Candlestick Park history with his bullet two-run single off flamethrowing Mitch Williams in Game 5, sending San Francisco into its first World Series since 1962. Watching in shock in September ’93 when a pitch from San Diego’s Trevor Hoffman sent Robby Thompson to the hospital with a fractured cheekbone, then winning that game with a walk-off homer in the 10th. (To this day, with the likes of Bonds and Dusty Baker leaping and shouting like little kids, it ranks with the most powerful Giants celebrations in the regular season.)

People spoke of Will Clark’s swing in reverential terms, and he added a singular nuance straight out of a photographer’s dream. The way it worked, when he really crushed a dead-pull drive, certain it was bound for at least a double, he pulled his left arm out over his body, parallel to the ground, and let it freeze there for just a moment, even if it meant obscuring his vision.

Pretty cool, most people thought. For teammate Kevin Mitchell, the image took on a life of its own.

“You know, a lot of vampires, how they throw up their cape after they bite somebody, and fly off?” Mitchell told SFG Productions one night outside the dugout. “Will Clark’s got that little move, after his swing, he throws his arm up and then he’s peekin’, like a vampire would do. That’s why I call it The Cape.”

I believe my case is closed.